When we talk about CNC machines, we usually think about machines that are commanded to move to certain locations and perform various tasks. In order to have an unified view of the machine space, and to make it fit the human point of view over 3D space, most of the machines (if not all) use a common coordinate system called the Cartesian Coordinate System.

The Cartesian Coordinate system is composed of 3 axes (X, Y, Z) each perpendicular to the other 2. 1.1

When we talk about a G-code program (RS274NGC) we talk about a number of commands (G0, G1, etc.) which have positions as parameters (X- Y- Z-). These positions refer exactly to Cartesian positions. Part of the EMC2 motion controller is responsible for translating those positions into positions which correspond to the machine kinematics1.2.

A joint of a CNC machine is a one of the physical degrees of freedom of the machine. This might be linear (leadscrews) or rotary (rotary tables, robot arm joints). There can be any number of joints on a certain machine. For example a typical robot has 6 joints, and a typical simple milling machine has only 3.

There are certain machines where the joints are layed out to match kinematics axes (joint 0 along axis X, joint 1 along axis Y, joint 2 along axis Z), and these machines are called Cartesian machines (or machines with Trivial Kinematics). These are the most common machines used in milling, but are not very common in other domains of machine control (e.g. welding: puma-typed robots).

As we said there is a group of machines in which each joint is placed along one of the Cartesian axes. On these machines the mapping from Cartesian space (the G-code program) to the joint space (the actual actuators of the machine) is trivial. It is a simple 1:1 mapping:

There can be quite a few types of machine setups (robots: puma, scara; hexapods etc.). Each of them is set up using linear and rotary joints. These joints don't usually match with the Cartesian coordinates, therefor there needs to be a kinematics function which does the conversion (actually 2 functions: forward and inverse kinematics function).

To illustrate the above, we will analyze a simple kinematics called bipod (a simplified version of the tripod, which is a simplified version of the hexapod).

The Bipod we are talking about is a device that consists of 2 motors

placed on a wall, from which a device is hanged using some wire. The

joints in this case are the distances from the motors to the device

(named AD and BD in figure ![[*]](crossref.png) ).

).

The position of the motors is fixed by convention. Motor A is in (0,0), which means that its X coordinate is 0, and its Y coordinate is also 0. Motor B is placed in (Bx, 0), which means that its X coordinate is Bx.

Our tooltip will be in point D which gets defined by the distances AD and BD, and by the Cartesian coordinates Dx, Dy.

The job of the kinematics is to transform from joint lengths (AD, BD) to Cartesian coordinates (Dx, Dy) and vice-versa.

To transform from joint space into Cartesian space we will use some trigonometry rules (the right triangles determined by the points (0,0), (Dx,0), (Dx,Dy) and the triangle (Dx,0), (Bx,0) and (Dx,Dy).

we can easily see that AD2 = x2 + y2, likewise BD2 = (Bx - x)2 + y2.

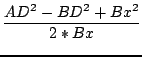

If we subtract one from the other we will get:

and therefore:

From there we calculate:

Note that the calculation for y involves the square root of a difference, which may not result in a real number. If there is no single Cartesian coordinate for this joint position, then the position is said to be a singularity. In this case, the forward kinematics return -1.

Translated to actual code:

return 0;

The inverse kinematics is lots easier in our example, as we can write it directly:

or translated to actual code:

A kinematics module is implemented as a HAL component, and is permitted to export pins and parameters. It consists of several functions:

Implements the forward kinematics function as described in section

![[*]](crossref.png) .

.

Implements the inverse kinematics function as described in section

![[*]](crossref.png) .

.

Returns the kinematics type identifier.

The home kinematics function sets all its arguments to their proper values at the known home position. When called, these should be set, when known, to initial values, e.g., from an INI file. If the home kinematics can accept arbitrary starting points, these initial values should be used.

These are the standard setup and tear-down functions of RTAPI modules.